This is the second in a series of reflections that came out of a fantastic sit-down with #MichED -ucators Melody Arabo (@melodyarabo) and Jeremy Tuller (@jertuller). Melody asked a question that followed up by mentioning that teachers have a really, really hard time answering: What parts of your professional work would you consider yourself to be an expert?

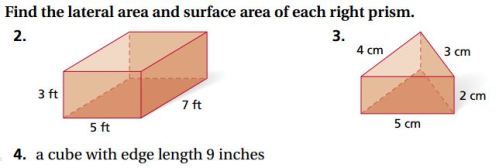

You see, the teaching profession makes it’s members uneasy by self-promotion. And it’s understandable. Teaching is a complex skill set. Teachers are renowned for having very, very broad sets of abilities as posters like this indicate:

Technology adds even more lines to this poster. So, with so many different nooks and angles to the work, it can be very understandable that teaching is a profession that makes it’s practitioners feel as though their efforts are stretched a mile wide and an inch thick. It’s hard to feel like an expert at anything under those circumstances.

But we need to. We need our expert teachers to not only be aware of their areas of expertise, but also be willing to advertise it. There’s a lot of teachers in this state. Lots. Like… tens of thousands. It shouldn’t scandalize us that each teacher has strengths and weaknesses. And some teachers have lots and lots of strengths. Every profession has it’s hall-of-famers. I could name a few that I’d nominate for a public school teaching hall-of-fame. Duane Seastrom… Eileen Slider… (Did you just think of a couple that you’d nominate?)

And teachers have a darn good perspective on this. They know who the good ones are and what they are so good at. “Kids never act out for her.” “The projects they do for him are amazing.” “She gets amazing growth out of students with disabilities.” But chances are, those teachers aren’t blogging about it. Chances are they don’t have business cards that say, “Mrs. Taylor, instructional designer, classroom manager.” Chances are they aren’t promoting the practices that they use that work. Chances are they aren’t standing up in staff meetings showing 5-min video clips of the awesome things their students are doing. Because teachers don’t do that.

What is it about teaching that makes it’s practitioners uncomfortable declaring their strengths and advertising them?

I have my own half-baked ideas. (Comment opportunities for dissent, if you’re in the mood.) For one, teacher evaluations are really time-consuming and we really haven’t figured out how to do it yet. What are the best practices? How important is student achievement? How do you measure positive impact of a teacher on an unsuccessful student? These are really, really tough things to measure. This is a symptom of our inability to collectively agree on the exact role that the teacher plays in the education industry. I can all think of the teacher whose in-class practice is pretty good, but it completely uninvolved in the community. I can also think of teachers whose instructional and assessment practices aren’t stellar, but they do a wonderful, wonderful job of reaching out to the marginalized students and keep them coming to school. I can also think of teachers who are inept in supporting the struggling students in their classroom, but because they coach three sports help keep an different population of struggling students eligible so that they can stay active on their teams. All three of those teachers are playing roles that are tough to evaluate. Obviously, we want every teacher to be hall-of-fame quality at instruction and assessment, but how do you isolate the “mandatory” skill set?

From the other side, collective bargaining has put pressure on teachers to not really separate themselves in any major way. If we find ourselves with a handful of teachers who are exemplary teachers, it’s very short logical leap to those teachers deserving some sort of reward for being so good at what they do. Naturally, there’s a very reasonable desire on a whole lot of different levels to shield the teaching profession from this. We want this field to become more collaborative. Not more competitive. So, to protect against that the unions have stayed far, far away from emphasizing outspoken greatness of individual teachers.

That doesn’t mean that greatness doesn’t exist. It just means that greatness is staying contained. We don’t want that. We want greatness to spread. And given the technology, given the pressure, given the difficulty of being a teacher, it is becoming more and more reasonable for teachers to begin identifying the exemplary practitioners and trying to figure out what of their skills can be displayed and transferred.

There are three things that I believe to be true. 1. It’s possible for every teacher to be a great teacher. 2. Not every teacher is currently a great teacher. And 3. It is in the best interest of every student in America to be in the classroom of a great teacher just as often as possible.

So, I’ll ask again: What parts of your professional practice would you consider yourself to be an expert at? What do you do really, really well that you could demonstrate to mentor up a young or struggling teacher? What are the things you do that are so good that you’d be willing to share them on the open educational marketplace of ideas? Feel free to reply in the comments section. That way if you have a weakness in the area that matches with a person’s stated strength, you can reach out to them and open that conversation.